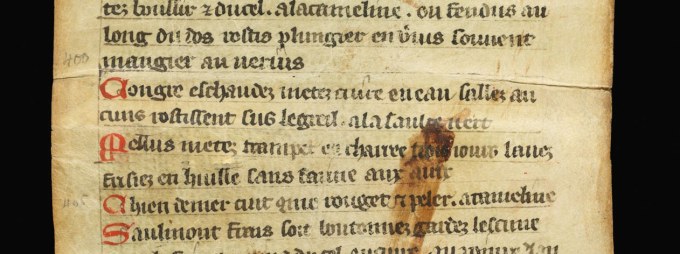

Eat Medieval – a partnership between Blackfriars Restaurant in Newcastle-upon-Tyne and Durham University’s Institute of Medieval and Early Modern Studies – is launching its first online cookery class. The course takes place from November 2nd to November 6th. It will focus on dishes from twelfth century Europe and features one of the earliest collections of culinary recipes from the Middle Ages. This is a set of sauces originally from the monks of Durham Cathedral Priory, from about 1170 which advertises itself as Sauces from Poitou. We also include individual recipes from two near contemporaries, Alexander Neckham drawing on his Paris student days, and Henry of Huntingdon whose verse herbal includes some reflection on culinary as well as medicinal use of herbs.

Continue reading “New online cookery course coming”Nucato: Candied Ginger Honey Nut Clusters

Mele bullito co le noci, detto nucato: Of honey boiled with walnuts, known as nucato.

– Libro della cucina del secolo XIV, 77

This is my adaptation of a 14th century Italian recipe for nucato, a ridiculously more-ish snack of crushed walnuts cooked in honey and spices, and cut into bite-size squares. Walnuts have been eaten by humans for thousands of years and were prized in medieval cuisine both for oil and for making sauces and adding to meat dishes… although eating too many was thought to be bad for the mouth…

The modern recipe for nucato was developed by Odile Redon et al. in what I find to be one of the better ‘modern medieval cookbooks’ around – The Medieval Kitchen – but here I gave it a twist by replacing Redon’s honey and spices with my Candied Root Ginger in Spiced Honey… and the results were spot-on what I was hoping for. Sticky, spicy, chewy squares of nutty goodness, with the occasional hit in the form of a ribbon of candied ginger. The perfect mid-afternoon pick-me-up.

Substantially increasing the honey content and spreading it out over a larger surface area to set would make brittle… bricato?…perhaps topped off with some smoked sea salt to finish? Hmm. Watch this space.

Candied Root Ginger Nucato

- 500g mixed chopped nuts (the 14th century recipe tells you to use walnuts, or alternatively almonds or hazelnuts)

- 500g Candied Root Ginger in Spiced Honey

- 1 lemon, chopped in half

Slowly warm the honey in a deep, wide pan until it begins to boil. Add the chopped nuts and mix thoroughly. Cook over a low heat for about 30-45 minutes, stirring regularly to stop the nuts sticking to the bottom of the pan. Be careful that the heat is not too high: you don’t want the nuts to darken and burn – they’ll taste nasty and bitter. Redon suggests that the mixture is done when the nuts start to “pop” from the heat of the honey, but I have to say that my nuts didn’t pop, and it still worked perfectly.

After 45 minutes, take the pan off the heat and spoon the nut mixture onto a large sheet of greaseproof paper – approx. 40 x 25cm. Spread it out using the cut side of half the lemon, to a thickness of about 1.5cm. Leave to cool to room temperature, and then pop it in the fridge until you’re ready to cut it into squares. Once cut, the nucato will keep for about 10 days in an air-tight container – technically, that is – mine lasted about a day before it had all disappeared!

Planting a Medieval Garden in Hamsterley Village

This weekend Hamsterley village, a tiny, beautiful place located between Teesdale and Weardale, celebrates its annual Flower Festival with a twist. ‘Magna Flora’ is a two-day event to coincide with the celebrations surrounding the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta and in honour of all things medieval, the village have transformed a corner of their Millenium Garden into a haven of horticulture medium aevum-style. I was delighted to be asked to help out, advising on planting and providing cuttings of some of the rarer herbs, and together we planted a fabulous raised bed, packed full of lilies, iris, cornflowers, and roses, as well as hyssop, southernwood, winter savory, costmary, thyme, sage and rosemary – Walafrid Strabo would have been proud!

Inspiration came from a wide variety of sources: from 9th century texts such as Strabo’s Hortulus, Charlemagne’s Capitulare de Villis, and the Plan of St Gall to 12th century records such as Alexander Neckham’s De naturis rerum, and, a little closer still to the signing of Magna Carta, Bartholomaeus Anglicius’ De Proprietatibus Rerum, and the results are stunning. The Millenium Garden is located just to the left of the Methodist Church in Hamsterley – should you ever be passing, do pay it a visit!

‘Magna Flora’ takes place on Saturday 27th, 2-5pm, and Sunday 28th June, 1-4pm. There will be exhibitions of miniature sheds, flower arrangements, plants for sale, and plenty of tea, coffee and homemade cake! Oh, and a talk by yours truly on the Saturday at 4pm on medieval cooking and it’s relevance for the 21st century. Here’s hoping there isn’t a civil war and that the barons don’t revolt…

Dining at The Jews House, Lincoln

Locating modern restaurants housed in medieval buildings is a great game, but the rules are strict. For a restaurant to sweep the board, the building has to have both retained its medieval character and be well thought out as a modern dining space, and it goes without saying that the food has to be good. You can advance to Go and Collect £200 if medieval cuisine gets a look in, but then the same rules apply as they do to the building. Finding medieval-inspired food on the menu is always fun, but it only gets the bonus points if it manages to straddle that slippery fence demarcating the subjective fields of ‘authentic reproduction’ and ‘gastronomic delight.’

A recent overnight stop in Lincoln meant an opportunity to put the rules of my game to the test. Lincoln is a medievalist’s paradise: Romanesque arches on every corner; a Norman castle fit for kings and convicts alike, and a cathedral that John Ruskin named ‘the most precious piece of architecture on the British Isles.’ Where old Lincoln tumbles down the hill to meet new Lincoln (down a cobbled street named ‘Steep Hill’, an understatement, if ever I heard one) is The Strait, once the Jewish quarter of the city and now home to a myriad of speciality, vintage and retro shops. If you can tear yourself away from the independent bookshops, you’ll find the The Jews House here too, a modern restaurant housed in the oldest extant domestic building in Britain, dating from 1158 (safely through the qualifying round).

Although the building has been modified considerably over time, much of the upper storey facade survives from the twelfth century: the double-arch romanesque windows and the chimney breast serving a fireplace on the upper floor which splits to form an ornately carved archway over the front door. Although the pillars supporting the archway have long gone, it’s not hard to see that this merchant’s house would have been one of the largest and most luxurious buildings in the area, and no surprise. This was the Kensington Palace Gardens of its day, where residents had serious cash to flash. Aaron of Lincoln (c.1125-1186), a Jewish financier and reputed to be wealthiest man in Norman England, lived only footsteps away up The Strait: these were neighbours to impress.

Nine hundred years later, making an impression is still high on the agenda, in the form of The Jews House restaurant and its offering. We had booked for a Friday evening and were taken immediately to a table upstairs, where the medieval hall would originally have been. The menu was short – a choice of 5 starters and 5 mains – but what it lacked in length, each dish made up for in terms of complexity: this is an ambitious kitchen at work. I opted for warm asparagus, crispy duck egg, beurre noisette mayonnaise and chicken reduction to start, followed by roast guinea fowl on pasta with morels, peas, fresh spring truffle and a wild garlic sauce… with hindsight, I should have kept my fingers out of the bread basket beforehand. But when the warmed house breads arrived, parcelled in a little hessian sack (nice touch), it was hard to resist having a rummage. And there weren’t just artisan rolls to be found – I also found the secret to keeping the rolls warm whilst on the table: a bag of hot marbles nestled at the bottom. Genius.

After such a feast of spring flavours, we couldn’t manage dessert, much though I wanted to prolong our stay and delay the prospect of climbing the hill back to the old town and to our hotel. The Jews House had excelled in the game of modern eats in medieval eateries, and the food, service and atmosphere were certainly in-keeping with the opulence and luxury that the building’s former occupiers would no doubt have also enjoyed. Given it’s place in medieval history, it would be wonderful to see what The Jews House chef Gavin Aitkenhead and his team could do with a few twelfth-century culinary touches here and there. If the contents of his hessian bags are anything to go by, the results would be pretty special.

A few photographs of the carvings on the west facade at Lincoln Cathedral, the traditional entry point. Incredible detail, although the last one is perhaps a little too graphic!

St Peter Stiftskeller: A dining experience 1200 years in the making

A recent week in Austria to celebrate a friend’s wedding ended with a final evening in Salzberg. Having spent the day soaking up another medieval and early modern palatinate complex in the form of the Festung Hohensalzburg and the incredible cathedral below, and making all sorts of noises about potential comparative studies with Durham’s own prince bishops, our thoughts turned to the prandial kind.

Nestled into a corner of the monastery walls of St Peter’s Abbey is the St Peter Stiftskeller, praised for its cellar by Alcuin of York in 803, and justifiably proud today of its history as Europe’s oldest restaurant. A flick through our guidebook and a peek at the Stiftskeller’s website suggested a slick, sharp, innovative restaurant and a matching clientele to boot. Karl Lagerfeld is just one of the many starry guests to have graced its threshold, and the web photography alone made me weak at the knees. For the Stiftskeller and I, I had a feeling it was going to be love at first sight.

Entering via a vaulted, open air courtyard, the welcome was warm and we were immediately shown to a table despite not having booked (and not being dressed in Lagerfeld’s threads). The menu was extensive and seasonal; classic meat, game and fish and vegetarian dishes, cooked up with international influences and a gastronome’s flare… a little foam here, a little glaze there…

Whilst we waited for a sharing platter of ‘Delicacies: surprise from the monastery’s kitchen’ and reflected on the happy nuptials, the charm of the city, and my newly-discovered appreciation for Austrian wines, we tucked into caraway and wholemeal breads with herb butters and dipping oil. In due course, the monastery’s kitchen was quick to yield its surprises, and, I’m glad to say, they were all of the pleasant variety. Beautifully arranged, we were treated to tiny portions of red pepper emulsion, carpaccio of beef, chilli jelly, cheese with a pear and ginger chutney, prosciutto, a herb mouse, tongue carpaccio, salmon and black pepper fishcake, and cuts of salted herring: tiny mouthfuls of intense bursts of flavour.

To follow, my husband opted to round his stay in Austria off with a hearty plate of tongue (if that isn’t too jarring a metaphor), whilst I chose smoked tofu in a thai coconut curry served with ginger basmati. Not quite traditionellen österreichischen Spezialitäten, but by that point the novelty of dumplings and wiener schnitzel had worn off and I was intrigued to see what the the kitchens could do with a block of tofu – not an ingredient I usually associate with high-end dining. Under the expert eye of Andreas Krebs and his team, however, it turns out that a form of magic akin to alchemy can be performed with good old bean curd.

We were too full to manage dessert, but I could have happily sat in the Stiftskeller all night. One wonders what the chefs at St Peter’s might do with medieval recipes on the menu, and indeed, what Alcuin might make of it, were he to see the monastic complex today.

A monk of fierce intellect: an advisor to Charlemagne, an advocate of educational reform, and the man responsible for introducing punctuation, capital letters and spaces between words to the written word, Alcuin was not a proponent of excess. He regarded the devastating Viking raids on Northumberland in 793 as divine retribution for the immoral and ‘luxurious habits’ of the Northumbrian people, and urged their king, Ethelred, to:

‘Defend your country by assiduous prayers to God, by acts of justice and mercy to men. Let your use of clothes and food be moderate. Nothing defends a country better than the equity and godliness of princes and the intercessions of the servants of God.’

Perhaps fittingly, one of Alcuin’s preferred foods was porridge, an old favourite in terms of sustenance and nourishment but maybe not the food of a senior churchman at the turn of the eighth century. But his poetry also suggests that in Utrecht he learnt to flavour it with honey and butter (‘In Traiect mel compultimque buturque ministrat ‘*), two ingredients that Mary Garrison observes as allegorical signifiers of wisdom and discernment.** I have no doubt that Garrison is right in this; the literature, both primary and secondary, on the role and symbolism of honey in the Christian Church is vast. However Alcuin was also clearly alive to the more holistic notion that what tastes good does you good. And in that sense, I think he would have been entirely approving of St Peter Stiftskeller’s hospitality 1200 years on.

*’Ad amicos Poetae’, Alcuini carmina, IV, in Ernst Duemmler (ed.), Poet Latini Aevi carolini, I, Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Poetae latini medii aevi 1, Berlin, 1881, pp. 220-222, here at p. 221, l. 9. **Garrison, Mary, ‘In Traiect mel compultimque buturque ministrat’, in Rondom Gregorius van Tours, eds. Mayke de Jong, Els Rose en Henk Teunis (Uitgeverij Verloren, 2001), pp. 114-117.

Long Pepper: A short-ish history

Piper longum: ‘We only want it for its bite – and we will go to India to get it! Who was the first to try it with food? Who was so anxious to develop an appetite that hunger [alone] would not do the trick? Pepper and ginger grow wild in their native countries, and yet we value them in terms of gold and silver.’

So said the Roman encyclopedist Pliny the Elder, of the fruits of the pepper plant, Piperaceae, expressed with his customary dose of dry wit. Much later, in the fourteenth century, the character known as Jehan de Mandeville, the alleged author of the popular later medieval travel account of fantastic voyages to the Far East, described the long pepper as looking ‘something like the flower of a hazel tree’ or catkin: a description we still use today. In fact, from at least 1000 BC, when the ancient Indian Ayuvedic texts praised its polyvalent ability to ‘provoke phlegm and wind: being pungent and hot, [… and] capable of increasing the semen,’ and until the 16th century, long pepper was a precious commodity in the global spice trade. A native of North East India, long pepper travelled both east to China and west to Europe, where its warming and digestive qualities were not lost on medieval cooks.

Guillaume Tirel, the fourteenth-century celebrity chef of the French royal court lists it among the basic spices of his store cupboard, along with ginger, cinnamon, cloves, grains of paradise, mace, spikenard, round (black or white) pepper, a finer cinnamon, saffron, galingale, nutmeg, and cumin. I always smile and think of Tirel’s list when people tell me that medieval food must have been bland or unadventurous. This may have been the French court, and one of the European epicentres of prestige, wealth and power in the Middle Ages, but if having fourteen different spices was considered de rigeur, one might wonder what Tirel considered exotic or lavish!

Similarly, Balducci Pegolotti, a Florence-born traveller and merchant, active between 1315 and 1340, includes long pepper among the exhaustive number of spices listed in his Libro de divisamenti di paesi e di misuri di mercatanzie, better known as the Pratica della mercatura. An encyclopaedic insight into the world of the Italian merchant, Pegolotti describes the types of imports and exports one might expect to find moving between the major trading cities of fourteenth century Europe and beyond, their names in both the Italian vernacular and in foreign tongues, the business etiquette of such regions, and all of the weights, coinages, and values required for successful commerce. Quite the Financial Times of its day.

Long pepper was also a favourite in spiced wines and digestifs. Half-remedy, half-inebriant, spiced alcoholic cordials have been around since the Romans, the most popular and enduring of which seems to have been the medieval ‘hippocras’, a red or white wine, infused with mixture of spices and sweetened with sugar or honey. But although the Greek doctor Hippocrates was many things, he was not the inventor of vinum hippocraticum. Rather, the etymology of this particular tipple was derived from the shape of the conical filter through which the spiced wine was strained, known to vintners as a manicum Hippocraticum – Hippocrates’ sleeve. Although production methods changed over the centuries, the name, and man’s enjoyment of it, stuck, and references to hippocras can be found well into the eighteenth century. A deliciously potent variant can be found in a late-fourteenth century English medical collection, found in British Library Ms. Royal 17.A.iii, f. 97v (edited in Hieatt and Butler’s Curye on Inglysch). A prescription for ‘Lord’s Claret’ (Potus Clarreti pro Domino), the wine is to be spiced with cinnamon, ginger, pepper, long pepper, grains of paradise, cloves, galingale, caraway, mace, nutmeg, coriander, brandy and honey. Kill or cure? I’m not sure, but you would certainly have had some fun trying.

Long pepper was also a favourite in spiced wines and digestifs. Half-remedy, half-inebriant, spiced alcoholic cordials have been around since the Romans, the most popular and enduring of which seems to have been the medieval ‘hippocras’, a red or white wine, infused with mixture of spices and sweetened with sugar or honey. But although the Greek doctor Hippocrates was many things, he was not the inventor of vinum hippocraticum. Rather, the etymology of this particular tipple was derived from the shape of the conical filter through which the spiced wine was strained, known to vintners as a manicum Hippocraticum – Hippocrates’ sleeve. Although production methods changed over the centuries, the name, and man’s enjoyment of it, stuck, and references to hippocras can be found well into the eighteenth century. A deliciously potent variant can be found in a late-fourteenth century English medical collection, found in British Library Ms. Royal 17.A.iii, f. 97v (edited in Hieatt and Butler’s Curye on Inglysch). A prescription for ‘Lord’s Claret’ (Potus Clarreti pro Domino), the wine is to be spiced with cinnamon, ginger, pepper, long pepper, grains of paradise, cloves, galingale, caraway, mace, nutmeg, coriander, brandy and honey. Kill or cure? I’m not sure, but you would certainly have had some fun trying.

By the late fifteenth century, long pepper’s hey day seemed to be over. John Russell’s Boke of Nuture (c.1460) provides a verse recipe for hippocras in which he states that:

Good son, to make ypocras, hit were great lernynge,

and for to take the spice thereto aftur the proporcionynge,

Gynger, Synamome, Graynis, Sugur, Turnesole (that is good colourynge);

for commyn peple Gynger, Canelle, longe pepur, hony after claryfiynge.

Its price was dropping, and, if the records of the household of the Earl of Northumberland in the early sixteenth century are anything to go by, long pepper was relegated to the bottom of the spice cupboard. The Percy house ordered just 8oz of the stuff in a single year, compared to a whopping 74lb of the beautifully named Grains of Paradise, imported from Africa.

The new kid on the block was another long pepper: the chilli. Coming from the newly-discovered lands of central America, chilli peppers were cheap, easy to propagate, and simple to cultivate in diverse climates such as Spain and Hungary. It added fire and colour, and, on the European market, long pepper couldn’t compete. It’s price fell to just one-twelfth of that of black pepper, a price that simply couldn’t justify the cost of harvest and transport. By the early modern period, it had all but disappeared from European kitchens, reduced to a relic of the medieval past to be copied out in recipes such as that for ‘red hippocrass’ in Nott’s The Cooks and Confectioners Dictionary (1703).

But after centuries of playing second fiddle to the chilli pepper and the black peppercorn, long pepper is enjoying something of a culinary and medical renaissance. Recent clinical trials have highlighted the anti-inflammatory properties of pippali (Piper longum Linn.), Indian long pepper, whilst the Indonesian variant, Piper retrofractum, originally commercially cultivated on the island of Java by the Dutch East India Company, is beginning to make its mark on the twenty-first-century foodie scene. Packaged up in modern, minimalist lines by spice retailers such as Steenbergs, Sous Chef, and the Peppermongers, these fragrant, pungent little catkins were hailed by Nigel Slater as ‘the most beautiful spice of all’ in his column in The Guardian. Working now with long pepper as part of the range of twelfth-century sauces I am developing, I have to agree.

Medieval food, Scandi-style

Like any medievalist worth their salt, a visit to Stockholm wouldn’t be complete without a peek into the Medeltidsmuseet, the Museum of Medieval Stockholm, located under the Norrbro bridge between the Royal Palace and the Opera House. The museum tells the story of medieval Stockholm from the mid-thirteenth century, and comes complete with excavated graveyard, warship, and cellars of the Blackfriars’ Monastery, all housed amongst the underground remains of the medieval city wall and churchyard of the Helgeandhuset (House of the Holy Spirit) – an area nicknamed the Riksgropen (the ‘National Pit’).

Betraying my modernist side, though, I’m a sucker for a decent museum shop, and the Medeltidsmuseet didn’t disappoint. The book selection featured recent publications on medieval food, including Maggie Black’s The Medieval Cookbook (2012) and Bridget Ann Henisch’s The Medieval Cook (2013), as well as a whole array of replica pots, jugs, jars. But most exciting were the little jars of poudre fort and poudre douce, and the sachets of long pepper on sale (Steenbergs – you have competition!)! Not something I’ve come across before in museum shops, in the UK or abroad.

The company who makes the food products is Bredaviks Örtagård, who run a reconstructed 14th century village on Sturkö, an island off the southern mainland of Sweden. As well as running a shop selling their food items, the village houses a medieval market place, a herb garden, and a dress-making workshop where you can buy modern linen clothing inspired by medieval patterns.

I also found Bredaviks Örtagård’s products stocked in the city’s Historiska museum, another hit on any medievalist’s itinerary of Stockholm. The Historiska takes a broader view at Sweden’s history, from the Stone Age to the Middle Ages to the present day. Their exhibition of the invasion of Gotland in 1361 was particularly striking – I haven’t slept properly since seeing the skeletons excavated still wearing their rusting armour! And the Gold Room… bling on a different level. But back to the food…

The Scandinavians have a complex medieval food history, detailed in the sagas and the chronicles, as well as in the vernacular recipe collections, much of which intersects with the English tradition, as Constance Hieatt outlined in her essay, ‘Sorting Through the Titles of Medieval Dishes: What Is, or Is Not, a “Blanc Manger”?’ Hannele Klemettilä blends the medieval Scandinavian tradition beautifully with the rest of the Western culinary collections too in her recent book, The Medieval Kitchen: A Social History with Recipes – a well-researched and accessible overview of high-late medieval cuisine, with plenty of manuscript illustrations to liven things up! So, I have my work cut out: eat medieval becomes äta medeltids!

Peter Brears at Blackfriars, Newcastle

On Saturday, 25th October 2014, the acclaimed food historian Peter Brears is coming to give the Blackfriars Lecture at Blackfriars Restaurant, Newcastle-Upon-Tyne. Continue reading “Peter Brears at Blackfriars, Newcastle”